Do We Really Need Multiple NAMES For CHORDS That Use The SAME NOTES?

Scroll down down down for the video...

Do we really need multiple names to refer to chords made with the same notes?

If I take the notes A, C, E, and G, depending on the how the notes are played (which is higher and which is lower) I could name it:

Am7,

C6,

Emadd11,13no5 (please don’t use this....),

Am/G,

C/A,

Am7/C,...

... you get the idea.

What is the point of all this? Is it really necessary to have this many names for what is ultimately the same thing?

If it’s the same notes, how different could each iteration possibly sound?

And to make matters worse some of those names could actually refer to the exact way these notes are played, such as C6 and Am7/C!

Shouldn’t we just come up with one name that can refer to every permutation and call it a day? This might sound like a good idea, but unfortunately it just doesn’t work. And for more reasons than ‘a day’ being a really stupid name for a chord. (ba bump pshhh!)

The main reason is that there are different contexts that this group of notes can be used in. And there are different sounds that can be achieved by reorganizing the chord.

All this calls for different names, because these different names do a better job of describing the function of the chord in the context it’s being used.

(if you have no idea what "context" means in practice, have a look at the video)

So, even though it seems like a great idea to simplify the way we name chords, the system already in place exists for a reason. And if history has taught us anything, it’s that you should always blindly trust that current systems and policies are inherently just and were created with your best interests at heart. is that sometimes things are the way they are for a reason. Not always, but sometimes.

If you want to understand the chord naming system much better and why it actually works extremely well, despite the apparent clunkiness of multiple names, watch the video linked below and I’ll explain the concept much further.

Want to understand this concept in significantly more detail, while also learning everything else you need to know about chords and harmony on the guitar? Check out my Complete Chord Mastery guitar course!

Video Transcription

Hello Internet, so nice to see you! I got an interesting question about chord names. I noticed the alternative names to the minor chords that showed up on the left of the screen, and that the first position A minor 7 was also described in other ways.

I presume it would depend on the key of the piece you were playing as to the name of the chord. Also, why was the A minor 7 described as A minor 7 slash E rather than just A minor 7? Okay, so first of all, let's see exactly what the ZL means.

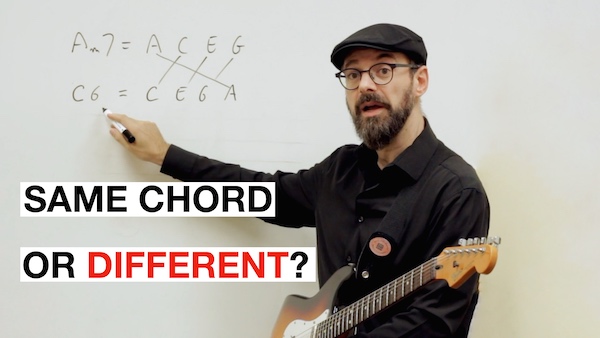

The slash, it's a way to indicate chord inversions. You may notice already, and if you notice already, stick with me for just a minute because we're gonna go see more interesting things in a second. But if I have an A minor 7, my notes are A, C, E, and G.

I can play these in a ton of different ways on my guitar, okay? Because I have so many different positions for these. And all of them sound slightly different. And one of the way to catalog and understand this position is to first divide them by inversion.

So what's the inversion of a chord? The inversion is determined by the lowest note you play in that chord. If I play this A minor 7 and the lowest note I play is an A, so if on my guitar I'm playing something like this, 5, 5, 5, 5, the notes are A, G, C, E.

The lowest note is an A and it's just indicated as A minor 7. But if I want to put a different note at the bass or change the inversion, for instance, I could play A minor 7 with a bass of E, so I put a slash, this is also called slash chords, and after the slash comes a note name, like this E.

The notes are the same, but now the lowest note must be an E. So a way to play that would be to do these. For instance, 12, 10, 12, 10. The bass note is an E. Okay. Then I have a C, a G, and an A. So the same notes, but the sound is different.

That's the root position. And that's this inversion here. Okay? That's what the slash means. In some situation, and for some chord, something even more interesting happens. Okay? Because, true, if I put together those notes, that's an A minor 7.

But that's not only an A minor 7. This would also be a different things in general, because if I write a C major, for instance, I have the nodes C, E, G, which you may notice are the same as here. If to this C major I add a sixth, okay, I play a C sixth, I have also an A, and now this A is the same as here.

So now, A minor 7 and C sixth have the same notes. But those two sound distinctly different because those are two different chords. Even if they have the same notes, I mean, even if they're just inversions of each other, because A minor 7 with a bass of C would be C6, C6 with a bass of A would be A minor 7th, they sound different, because one is a minor chord, and so it definitely sounds minor, and the other is a major chord.

So it definitely sounds major. This doesn't feel like moving between inversion. This feels like playing a different chord. And depending on the situation and where I play them, that's A minor 7, okay, but in other positions like this, that's a C, major 6th, and again, depending exactly where I play this, it will sound more major or more minor.

Okay, so at this point, if I call it one way or another, it will depend on the context. It will depend on what I played before that, where I'm coming from, how I'm leading my voice, or somehow how the chords connect together.

And then your ear will interpret those four notes in a specific configuration as sounding more happier, more major, more C6th, or sadder or more minor or more A minor seventh. Formally speaking, if I just look at the notes, either name is good.

So when you play this into your computer, say, or you write it into a square to your computer, and the computer who has no idea of the context looks at the notes and gives you those two names, so it writes C6th or A minor 7 or something else, the computer is just trying to give you all the possible naming for this group of four notes.

In reality, your ear will have listened to the music up to there and will interpret this chord as being major or minor, even if the four notes are the same. If you want, it's kind of a musical illusion.

Ear assigns a specific meaning to those notes, depending on the context. Some music theorists have spent a lot of time trying to determine exactly when your ear determines that the chord is a major and when your ear determines the chord is minor.

There is some interesting research on that, but it's really way too complex. And the simplest thing for us musician to work with it is just play it and hear it and see what happens. Just play the inversion you're interested in, okay?

And then you can decide which one of those will sound more major or more minor, in what position it will sound more major or more minor. Okay, and what to do with that essentially. Okay, those are all inversions or positions for those chords here.

This happens a lot of time in music theory. This happens very often in music theory. And often if you learn something about chord, you will see people write stuff like C6 equal A minor 7. And again, it doesn't mean the two chords are exactly the same.

They can sound different. It just means that the notes are similar. Okay? And there are several equivalences like that. Another one, for instance, that C minor 6th, it would be the same as A minor 7th with a flat 5.

Okay, the notes of both being A, C, E flat, G. And so you have several of those equivalences in music theory. And once you know them, that makes it easier to work with substitution, so change one chord for another and do some interesting effects with music.

If you want to know way more about substitution and actually how to use them, we cannot cover how to use substitution in a 10-minute video. But if you want to know way more about how to use substitutions in music and to create interesting effects in your chord progression, how to take a song that has a chord progression and change this chord progression so the song sound different, but it's still the same melody and is still recognizable as the same song.

Then I recommend you guys have a look at my course, Complete Chord Mastery, where we cover these and much more and we go through substitution and see, you can see how they can take a chord progression, an existing chord progression with an existing melody, and change the chords under there to create interesting effects.

You find the link to Complete Chord Mastery in the description of this video. This is Tommaso Zillio for musictheoryforguitar.com and until next time, enjoy!