Understanding The Rules Of Musical Notation: Why Ab And G# Are Different?

If you are anything like most guitar students (well, not MY students, that is…), then you are probably at least a little bit confused by musical names, particularly how we spell out chords, keys, and scales.

For instance, take the fact that G# and Ab mean the same thing, except they really don’t because they don’t sound the same, but they are the same frequency, but we can’t always use either one in every situation…

… it’s all just a lot of confusion (in the mind of most musicians), and I would like to clear up at least a few things.

Because, believe it or not, calling a note G# or Ab does make the difference. But what a controversy this is, for something that should be quite basic.

For instance, recently, I was on stage explaining this to a fairly big audience when a big burly man from the last row bellowed: “This is B.S. It does not really matter what we call things. It’s just a name! This is all just semantics!”

Me: “Thank you for your comment, my dear Sonja. May I venture the opinion that you never took the trouble of finding out what ‘semantics’ actually means? Because, I mean, you are making my point for me…”

Him (vaguely stunned, interrupting me): “Did you just call me Sonja?”

Me (with my best $#1t-eating grin): “According to you, it does not really matter how I call you. It’s just a name!”

After the laughter died down, a tall skinny man raised his hand and said: “Well, what you say is not completely correct. These two notes are different only in Just Temperament. But in Equal Temperament they are the sa…”

… and this is when I gave the signal to my sniper to take him down.

Yes, I take a radical approach to hecklers. And yes, the moment they mention “temperament”, I know they are hecklers.

See, I used to troll these hecklers by asking them if they knew the difference between a syntonic comma and a ditonic - not diatonic - comma (anybody who mentions “temperament” should know about that… or they don’t know what they are talking about!)

That was fun for a while, but it’s easy to lose the audience. I mean, we are there for the music, not the math, amirite?

I found the sniper is a more efficient solution, and it keeps the rest of the audience on their toes. “Any question?” “Nononono!”

But back to us.

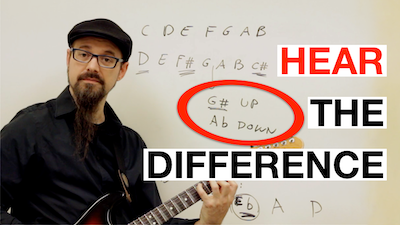

In the video below, I will make you hear the difference between G# and Ab. That happens at 11:34.

But I do recommend you watch it from the beginning, or it won’t make much sense. See, to make sense of sharps and flats and note names, you need to use them the way they were intended…

… and that includes the 2 magic ‘rules’ that I will explain in the video:

The ‘same distance’ rule

One of the benefits of our system of musical notation is that an interval of a third will always be the same distance from the original note: 2 letters. This means that a major or minor third from any note will always take you 2 letters forward.

The same rule is true for every single interval. This makes it significantly easier to memorize and recognize intervals!

The ‘one of every letter’ rule

This is a rule that makes it much easier to see how scales and keys are built, but for this rule, you will have to watch the video below (hey, I can’t give away everything right away…)

If this all sounds like terrifying made-up music theory jargon and nonsense, check out this free eBook on notation, tablature, nashville numbers and chord symbols, which will be an helpful start with notation.

Transcription

Hello, internet so nice to see you. I have an interesting question I want to answer.

I know you can’t use letter twice in minor and major. But why does D sharp harmonic minor have a C double sharp, not a D?

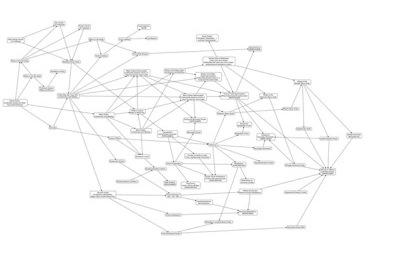

Our notation system for the name of the notes is weird. I agree with you. And indeed, I have a number of people in my YouTube channel, commenting on a few videos I made that in their opinion, that our notation system is wrong, a relic of a past era and something that we should ultimately let go in favor of a different notation.

And yeah, I have mixed feelings on that. Because on one side, it’s true that our notation system for notes is weird. But on the other side is that the notation system is made this way for a specific reason, and that it helps us making music.

Okay, so let me show you what is the good part of our notation system, and then if you want to change or not, however, up to you. I had people commenting again, on my comments that they will not ever learn how to read music, and they will just use a piano roll. But the thing is, this goes beyond if you use the notation, tablature, piano roll or you don’t use any notation, the idea of the name of the notes, is that it helps you make music; so let me show you how.

Rule number one here and again, I struggle in calling those rules. But let’s say the way we do it is that we use only one letter per note. So if you have a scale of seven notes, and we’re using commonly seven letters, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, okay, then it’s great, you use one of those letter per notes, and then you are just using sharps and flats, okay? However many sharps and flats you need to use, okay, that’s the basic rule.

Of course, if you have scales of eight or more notes, like a diminished scale, well, then all the rules go out the window here, okay? Also because the diminished scale is a symmetric scale. And this stuff doesn’t really apply anymore, as you’re gonna see, the intervals are weird there.

But if you have a seven note scale, which means major scale, minor scale, all the harmonic, minor melodic minor, all the modes, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Phrygian dominant, Lydian Dominant, Lydian augmented 5, all those kinds of modes, these rule of one letter per note applies.

Why we’re doing this? Well, you know, it has to do with intervals, okay? It’s, it’s to recognize immediately what intervals we are using. Okay, so that’s the first thing.

For instance, if you go up a fifth from a C note, you’re always going to find the G. Now if it’s a perfect fifth and you go from natural C, you’re going to find a natural G. But if it’s an augmented fifth for diminished fifth, or if the C was a C sharp or even, in some case, strange case, a C flat, the note a fifth higher is always going to be called G. Okay?

So once you memorize the letters and the distance, if you’re trying to build chords, and you know that the chords are built in thirds, so you’re always, you’re always jump a note, okay you always jump a letter C, E, G, B, and you’re building chords this way, you already know what is the next letter, you just need to figure out if there are sharps or flats.

Once you use these for a while, it becomes second nature. And it becomes super easy to do to build chords or do other things. Because the intervals are already built in, baked in the letter system.

But I agree with you, the whole thing is weird. And it is weird because we are using the sharps and flats to do two different things. Okay, so let me explain those different things because, I don’t think, I mean, everybody knows that once they reach a certain level of experience, but I haven’t seen these explained clearly.

So the first function of sharps and flats is to tell you what notes are in the key. Meaning, if we’re working in C major, if you’re playing something in C major, the notes are simply the letters, okay? C, D, E, F, G, A, B.

Good, but if you’re working for instance, in D major, the notes are not the same. The notes are D, E, F sharp, G, A, B, C sharp, and we have a sharp here and here, because we need to adjust the intervals between those notes so that this sounds like a major scale.

Okay. If you have any doubt about these, I have a video that is called the theory from zero, okay, where we cover all those things. So in that case, go there.

That’s function number one of sharps and flats. tell you, what are our basic notes in that key, our starting notes, where is our ‘home’, okay in that key. those are the home notes, okay?

But then we use sharps and flats for another function, which is to alter the note in those key. And before we go ahead, let me tell you that in my opinion, we should have used two different ways. Okay? We should have used the sharps and flats just to alter the notes and find another way to write the notes in key or vice versa. Because the confusions come from the fact that we’re using sharps and flats for both those things.

Okay, but what do I mean with altered note? Well, when I’m writing music, sometimes, I mean, I’m just using notes of the scales, but sometimes I want to use note outside the scale, because they have a very specific flavor, and they sound good, okay?

So when we go out of key, we take one of those notes, and we alter it, okay, this is not something we invented. Okay, this is something we discovered, meaning that whenever I use an extra note that your brain tries to, tries to categorize that new sound that is not in the scale as being one of those as being the root or the second, or the third, or the fourth, or the fifth, or the sixth, or the seventh of the scale. Okay, thats not something we invented. It may be cultural, I don’t know. But that’s what our brain does. Okay.

It makes sense to write this note as being an alteration of an existing note. So for instance, if I want a note between the G and the A, in this D major scale, I could call these note, either a G sharp or an A flat. And of course, by the way, I’m doing everything in our 12 note equal temperament. So yes, those are the two have the same frequency, those two are played in the same way on the fretboard is the same key on the piano, your brain still interprets those differently, okay, as you’re gonna see.

I’m gonna use the sharp note if this notes gonna resolve up, so if after this D sharp, I’m gonna play an A, so the note, it’s out of the of the scale, but resolves or comes back in the scale by going up, I’m going to use the sharp, okay? There’s a reason for that we’re gonna see.

If the note instead goes down, I’m gonna use the flat. Okay. And again, this helps us find the right chord or the right harmonies for those notes, how? When, let’s say I want to write a G sharp, I want to use a note as it goes out of the key. Okay, and then re-enters the key by going up. So let’s say I have a chord progression, some chord progression, like D, G, something else, A and then back to D. And in something else in something else, here, I want to have a chord that contains this G sharp, okay?

Now with a little bit of experience, you can pick different chords, but a good a good chord that will work here would be E major, E major is E, G sharp, B, okay? So I’m gonna put this chord E here, and I’m going to put the melody note being G sharp, okay?

So what’s gonna happen is that the melody note here, it’s something it’s something here, here, the melody note is G sharp, and here the melody note is A, so we’re gonna hit this G sharp moving up to A, okay? So let’s say I have my D then, I have my G, and I have my E major, and my A. And you can clearly hear the G sharp in E major going to the A in A major. And then I go back to D major, or whatever. Okay?

Memorize this feeling. That’s that note out of key resolving up. If we call it A flat, we wouldn’t use an E major because in E major, you have a G sharp, not an A flat. Again, learning your chords with the right letter and not confusing G sharp and A flat pays off.

What if I want an A flat? Okay, now I’m going down. And there are many ways to go down. Okay? One of them. So we’re going to have a melody note of A flat, and the next melody note is G. So we need to find a way to make that work. Okay?

So, one way is to start your chord progression in D, we are in D major, let’s start on D, okay, here you’re going to have a strange chord, you’re going to have an E minor, with a melody note of G. Here we can put an A with whatever and then come back to D.

Okay, so now what do we use here? And by the way, I’m actually going to change something here and I’m going to play actually something different. I’m going to put an E flat here. I just changed my mind at the last possible minute, this is now completely live improvised. Because I just think hey, this will sound even better, okay, I’m using even a different chord here.

Now this for the people who don’t know, that’s a Neapolitan chord, okay, it’s always the flat second of the key. But I know this will sound good, okay? Here, that’s an A flat note, we need to find a chord that has the A flat note in. And again, that’s not the G sharp.

So now, you can search around and then write down all the chords well an A flat note, here, I’m going to use a B flat seven, the seven as an A flat, again, if you spell it correctly, B flat is B flat, D, F, A flat, okay?

If I play things in this order, it will sound good. I’m gonna try and put all those notes on top. Okay, so I’m going to have my D major, I’m gonna have my B flat seven. It sounds out of key, you feel it, it sounds out of key, okay, And I’m going to have my E flat. And I’m going to have my a major, maybe 7, and then D. Okay, I’m in D major, and I’m gonna play this again.

Memorize this feeling, this note wants to resolve down, okay, into this.

Let me play the previous example, and this note here is now a G sharp.

If I cut away all the sounds before and after. This is the same physical frequency, it’s the same, whatever you want to call it, it’s not a note yet, okay? It’s just a vibration in the air. It’s the same vibration for A sharp and G flat. But the psychological feeling you get from a G sharp and A flat are different. And so we are calling them different because once you spell your chords correctly, it’s easier to find the chord that harmonizes them, okay, B flat seven does not contain a G sharp, B flat seven contains an A flat, if you spell it correctly.

So spelling those the right way helps you select the right chords. Automatically in the system, all the chord that will work with the note going down of these notes spelled A flat, and all the chords that will work with this note going up has this note spelled G sharp.

It’s like the system is doing the work of selecting the right note the right chord for you by simply labeling those chords in different ways. Okay, now, of course, you’re not going to see this until you do these kinds of things, until you go out of key.

So if you always write in key, you’re not going to see this difference. If you never do this kind of thing, you’re not going to see the difference. So for you, it makes no difference. Of course, you’re gonna think, hey, this system is strange and cumbersome, and complex and weird and mysterious, and why they’re using it, we’re using it because when you go out of key, when you alter your note outside of the key, it helps you find the right chord.

Those are but two examples. Okay, there’s way more way, way, way more, okay, because you can go out of key in 1000s of different ways. Now, if you want to know all this, I mean, this is just scratching the surface. This is just a few minute video on YouTube guys. Okay, I can’t really sit here for hours and hours and explaining all the possible ways. But if you want to know all the possible ways you can, because I sat down hours and hours and recorded this in my course complete chord mastery.

In complete chord mastery, which is my course made for guitar players and we do all the harmonies directly on the fret board. Okay, you see all those things and you see all those ways to go out of key and in, back in again or change key and you see how to play those chords all over the fretboard.

Triads, seven chords, altered chords, okay, anything you want directly on the guitar fretboard so that you can write your music directly here without having to worry about notation and stuff, notation is useful! I’m not saying no. The notation is useful. But you see that once you get used to this, this becomes a powerful tool, Okay?

But here’s the thing, if you take complete chord mastery, you don’t have to learn how to read music. If you want you can. I’m not forbidding anybody, and I have this course too in the course but you don’t have to you can follow the whole course without Knowing how to read, I’m explaining everything there. So if you want to become a master of harmony on guitar, check out complete chord mastery.

And now, if you liked this video, smash that like button, don’t forget to subscribe and click on notification. And if you have any questions, write them down in the comment.

If this explanation was clear, let me know, if this explanation made just a big mess for you, just let me know I’m going to check your questions. And I’m going to keep explaining until you guys understand. And then, you can take you can make your choice if you like this notation system or not, after all, you’re not here forcing anybody I’m just trying to explain the advantage of the traditional notation system. And that’s everything. This is Tommaso Zillio, MusicTheoryForGuitar.com, and until next time, Enjoy.